It’s hot. The air inside is stuffy, and the atmosphere is dull and heavy. The sound of muffled groans, moans, and sniffles can be heard through the flaps of a medical tent. As you enter the path is immediately impeded by cots holding men. They had been crammed into an improbably small space. Too few nurses circulate among the beds, doing their best to comfort the distressed soldiers and the occasional civilian. Standing in a quiet corner scribbling in a notebook is Mary Bruce, everyone’s go-to. Mary is head of the Operating Theater9, and her husband, Colonel6 David, is a Royal Army Surgeon.

In the late 1890’s Mary and David tested their newly minted marriage to serve in the Second Boer war as medic7, but the story of their scientific partnership and surprisingly modern marriage started far before the world-famous Siege of Ladysmith.

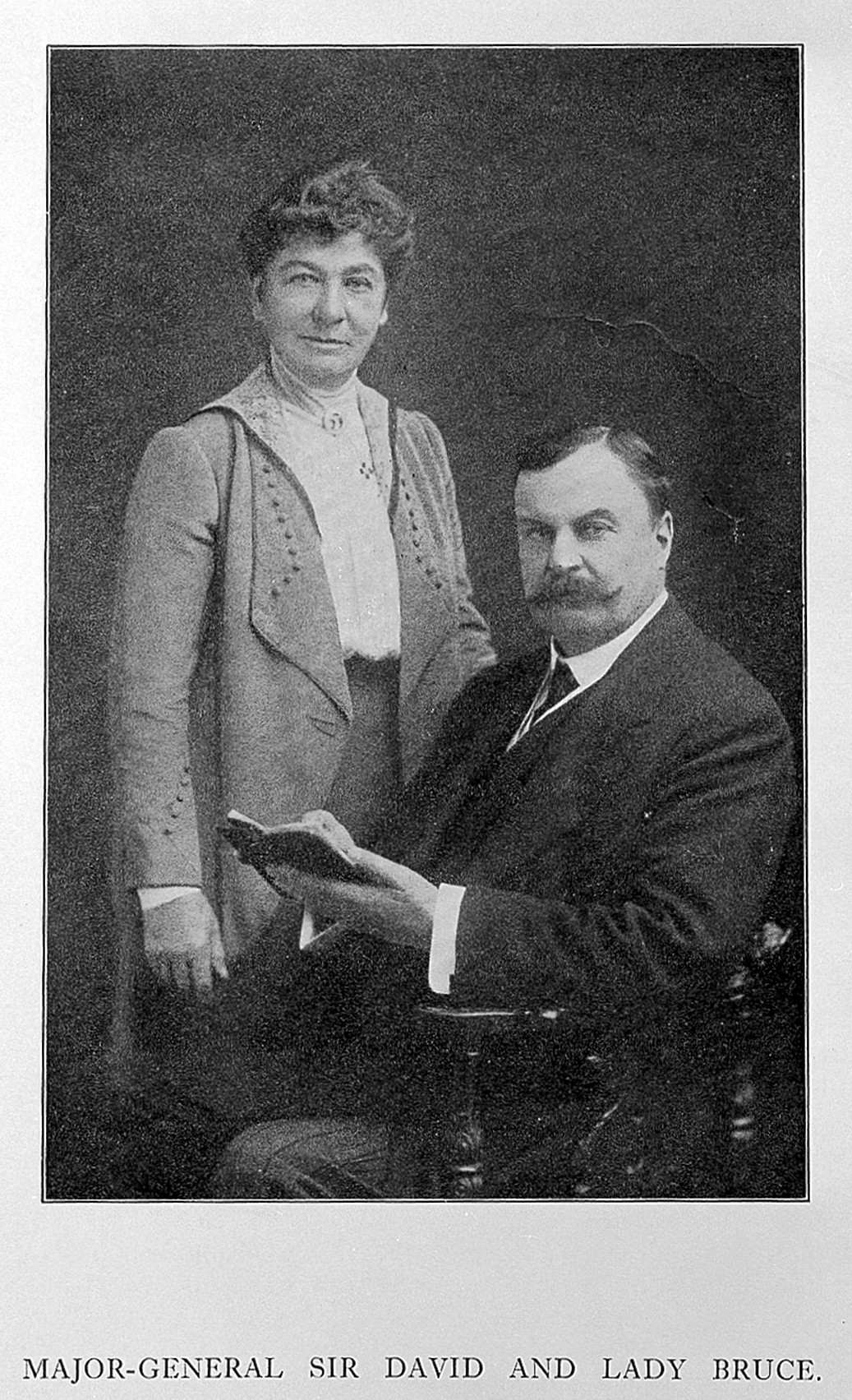

The late 1800s was no place for a woman trying to make her mark in society. Mary Elizabeth Steele Bruce was the wife of microbiologist Sir David Bruce, with whom she worked alongside as they traveled the world conducting research and contributing to science in a number of ways. Sir David Bruce, as a scientist and physician, was credited with multiple fundamental discoveries in tropical medicine throughout his career. Mary Bruce, though a woman, was instrumental to David’s success, assisting him in all of his work and research. She did everything from simple note taking, to scientific illustration, to being a key contributor to published papers. David was known for saying that he always wanted to make sure that his wife got the credit that she deserved2. It is time she was recognized and accredited for her role in tropical medicine history.

While the specifics aren’t known, Mary Bruce received some type of education, growing up as she did in a well-to-do family. Her younger years were during a turning point in history. Girls were only expected to marry their husband and be a “wife”, which meant that they needed to have skills such as piano playing, flower arranging, painting, or singing. There is no record that Mary Bruce went to university, but her scientific knowledge could have easily been obtained around her home. Her father, being a doctor9, likely had science and medical books around for Mary to sneak off with. It is possible that her father taught her. Even her brother turned out to be a doctor, so maybe science was just in her blood. David was exactly the same way, which is precisely why the two were a perfect match. The couple met when David was working for Mary’s father at his family practice in Reigate, Surrey, England7.

Mary and David’s life together was happy and full, but the two never had children, an unusual occurrence for the time period. Not having children meant their work was unhindered by family responsibilities, enabling them to travel together with relative ease. Mary was not considered a girly girl. She was said to be a great shot, and never worried about her appearance, even chopping her hair short2. She was his constant companion and worked as his technician in the lab, which is when she created many of the illustrations of his microscope work9. Mary defied the times by traveling with the men instead of staying safely at home2. Some said that Mary was always the one to keep David level headed; one colleague stating, “She certainly curbed his intransigence and his impatience.”7 David’s work for the Royal Army sent them to Malta, Germany, and all over sub-Saharan and South Africa. They traveled by horse, and train and even on foot when necessary. Each country presented a new challenge. Sometimes, their roles were doctor and nurse; other times their roles were scientific collaborators.

Early in David’s career he worked for the military field service7. The couple moved to Umbombo Hill where they were assigned to investigate an illness that was a highly prominent disease running rampant through cattle and horses of the area, however their timing and location caused them to be swept up into the chaos of the Second Boer War7. Being able to help, they worked tirelessly to take care of wounded and sick soldiers. Mary was Sister in Charge of The Operating Theater, or head nurse, while her husband was the operating surgeon in a field hospital he ran during the Siege of Ladysmith7. Mary and David’s effort in the medical tents was no easy task however. Both lost significant amounts of weight due to strict rationing, the long hours of work, and the ravages of disease. From a letter originally destined for her sister, Mary wrote that David was in charge of 1000 patients and had worked 30 hours straight in surgery until relief was finally sent. She reported her weight went down “7lb and 1 stone” (around 21 lbs)1. Their work did not go unnoticed, however, because David was promoted to Major-General and seconded to the Royal Society Commission which was located in Uganda around 19038. Later on in their life, the pair was again called to service during World War I. David’s role became Commandant of the Royal Army Medical College, though it is said that he would have preferred to be in active service. Despite this he was knighted in 19086. Simultaneously Mary worked on Committees focused on control of trench fever and tetanus, for which she was awarded the Order of the British Empire8.

Apart from his wartime efforts, and during the larger part of his scientific life, David Bruce was responsible for identifying the bacteria that caused of undulant fever (Micrococcus melitensis aka Brucellosis) and establishing that the parasites that cause Sleeping Sickness and the cattle wasting disease nagana, are both carried by the tsetse fly5. Both of these pathogens (Brucella (Micrococcus) melitensis and Trypanosoma brucei) both were named after Sir David Bruce to honor his scientific work. Along with these major discoveries, David was renowned in the UK and amongst his colleagues all over the world for his service in the Royal Army throughout his life, including his service as an educator and leader at the Royal Army Medical College8 during WWI, and his Chairmanship of the Mediterranean Fever Commission6. David Bruce did so much with his life, but where was Mary during it all? Though her contributions are harder to track, Mary was a vital part of the many scientific discoveries made by David Bruce.

Mary Bruce held the title “Lady” because of her and her husband’s honors. When David Bruce earned the title of “Sir”, it was customary to call the wives “Lady”4, however “Lady Bruce” was so dubbed with an “Order of the British Empire” around the time of WWI8, and this was because of her own scientific impact; not only on the WWI committee, but because they recognized her as a true woman of knowledge. She was a talented artist and illustrated most of the microscope images that can be seen in her husband’s published works, implying that she was actively working at the microscope. In some papers, she is formally credited for the illustrations. In others’, only her M.E.B signature can be seen; but in some, she is uncredited, yet her distinctive artistic stamp is readily apparent in the elegant drawings. Starting around 1913, Mary began to receive authorial recognition on her husband’s published papers, a time when the couple was working on human Sleeping Sickness. According to one account, Mary was also part of the actual discovery that tsetse flies were the specific carriers for the sleeping sickness trypanosome3. Beyond this she was sacrificial with her time, as no task was too minuscule for her. This was seen in the lab, when David asked her to dissect another 10,000 tsetse flies, as well as in the hospital setting where she would do any menial job to relieve the strain of another.

David’s many successes were in full partnership with his smart and talented wife, who was always working by his side. Therefore, we cannot consider his many discoveries and accomplishments without also considering Mary and her many contributions to those very same discoveries and accomplishments. Though Mary may never have felt the appreciation of her work by her colleagues that she would have in today’s age, recognition for her life’s work in scientific discovery can be acknowledged now. In a tragic but romantic twist to their unconventional story of love and science, Mary and David’s deaths were but days apart, because David could not go on without his forever love and faithful partner, Mary. Today, we can look back at the impact their work made in science and be thankful that the world was lucky to be marked by such a paramount and influential pair.

Work Cited

- Bruce, Mary. Letter to Dr. Russell Steele. 7 May 1900. Personal Collection J R Army Med Corps.

- Grogono, Basil. “Sir David and Lady Bruce. Part 1: A superb combination in the elucidation and prevention of devastating diseases.” Journal of medical biography, vol. 3 no. 2, 1995, pp. 79-83.

- Grogono, Basil. “Sir David and Lady Bruce. Part 2: Further adventures and triumphs.” Journal of medical biography, vol. 3 no. 3, 1995, pp. 125-132.

- Guest submission. “A Guide to the Order of the British Empire.” Royal Central, 14 Dec. 2019, royalcentral.co.uk/features/insight/a-guide-to-the-order-of-the-british-empire-21224/.

- kreitano. “A3: David Bruce.” General Microbiology, 23 Jan. 2018, microbiology.community.uaf.edu/2018/01/22/david-bruce/.

- London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “Sir David Bruce (1855-1931).” LSHTM, 2019, http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/aboutus/introducing/history/frieze/sir-david-bruce.

- Smyth, Alisdair James. “Lady Mary Elizabeth Steele.” geni_family_tree, 7 Oct. 2019, http://www.geni.com/people/Lady-Mary-Elizabeth-Steele/6000000024564396846.

- Vol, et al. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Section of the History of Medicine Wives of some Famous Doctors PRESIDENT’S ADDRESS. , 1959.

- Vella, E. E. “Major-General Sir David Bruce, K.C.B.” Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, vol. 119, no. 3, 1973a, pp. 131-144. CrossRef, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jramc-119-03-02, doi:10.1136/jramc-119-03-02.

Image Sources

a. All images are in public domain.