Ethics in Medical Practices: Part 1

By Krista Surprenant

Most of us have experienced a health kick at some point in our lives—reading nutrition information, counting calories, and tracking vitamin levels to hit the perfect daily intake. Maybe you’ve even looked up the health benefits of your favorite products. But have you ever stopped and asked yourself how those nutrient levels were determined?

For one brand, information on nutrient levels can be traced back ~75 years to a specific study done at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)1. Prior to MIT’s experiments in 1949, studies showed an acid found in oats had a negative impact on calcium, iron, and phosphorus absorption, sparking debate around the nutritional value of oat-based cereals [1,5]. This raised consumers’ concerns about major brands such as Quaker Oats. In order to defend their product against competitors like Cream of Wheat, Quaker Oats funded MIT’s study to track iron and calcium absorption following cereal consumption [1]. The company hoped to demonstrate that their cereal did not reduce mineral absorption and was nutritionally comparable to Cream of Wheat [1,5].

To carry out this experiment, MIT needed volunteers, so they turned to The Fernald State School in Waltham Massachusetts [1,5].

In 1848, the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded was founded by Samuel Gridley Howe with the goal of educating disabled adolescents to become high-functioning, independent individuals [6]. Students were taught academic, vocational, and personal skills, including sewing, housekeeping, music interpretation, and athletics [6]. Over time, the school expanded to house adults requiring custodial care and individuals with more severe disabilities. In 1888, Walter E. Fernald became superintendent of the school and shifted the institution’s philosophy towards a scientific framework rooted in eugenics [6]. Eugenics sought to promote “desirable” traits through selective breeding while eliminating “undesirable” traits—possessed by groups that included people of color, immigrants, and individuals with developmental or intellectual disabilities [6,7]. Those deemed “undesirable” were often institutionalized, including residents of what became known as the Fernald State School in 1925 [6].

During this same period, IQ testing became widespread, and children scoring below average were labeled “morons” or “intellectual delinquents” and frequently institutionalized without parental objection [6,7].

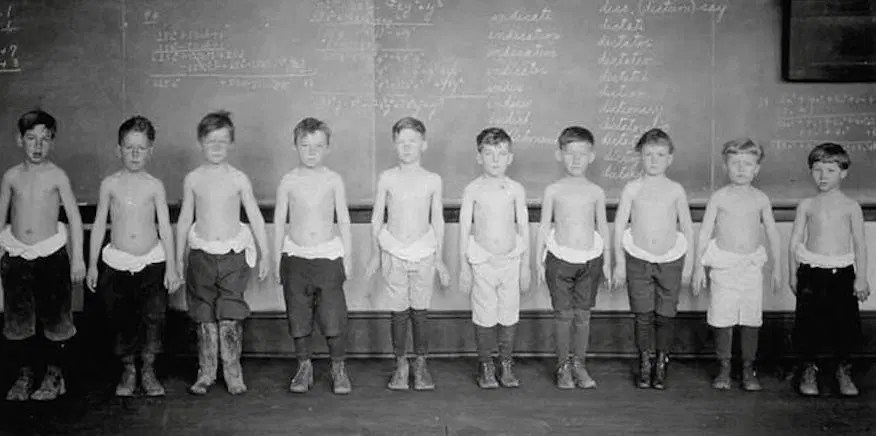

Due to the increased population of students admitted to the Fernald State School, the institution became overrun and underfunded [5,6]. Eventually, the school became home to 2,000-2,500 disabled and unwanted children who were, at the time, considered “not part of the human species” [5,7]. When it opened in 1848, the school’s aim was to provide students with a stable education and sustainable life skills so they could eventually be able to provide for themselves, and be morally rehabilitated (due to thinking disabilities are outward manifestations of corrupt souls). Over time, however, this educational facility that had originally provided nurturing care and solid foundations became a neglectful, abusive custodial institution. Eventually, due to inadequate funding, the incarcerated students who were not physically disabled were used as sources of manual labor to keep the institution functioning without hiring more employees. Years later, at a news conference, one past student at the institution stated, “Instead of being taught, we were being used, and I don’t think that was right. I don’t have the education that a lot of students have now because of my upbringing here. I wasn’t taught anything, I have trouble reading, I can’t spell, I try to get help, and I can’t get help” [5].

This created a perfect opportunity for exploitation of the students.

Because of the large numbers of easily obtainable subjects, MIT recruited disabled students from the Fernald School for an exclusive “science club” at the university. The students were enticed to participate through bribery. Science Club members were offered special privileges including beach trips, better dinners, and access to sporting events. In return for these privileges, the students would be required to participate in various scientific studies, such as the Quaker Oats nutrient tracer study [1,5].

In total, the MIT tracer study used 40 students, ages 7 to 17, to conduct three tracer experiments with the goal of understanding how the body absorbs minerals. The first experiment involved a few dozen students who were fed Quaker Oats cereal coated with small amounts of radioactive iron [1,12]. The radioactive iron chemically behaves just as natural iron would in the body, but its radioactive nature allows it to be traced. In order to trace the iron, the scientists collected frequent blood, urine, and/or stool sample from the participants, measuring the radioactive emissions using a special detector [1,7]. This study revealed that the absorption rate of iron from rolled oats was no less than farina (Cream of Wheat) [1]. The second experiment involved 36 students who received two breakfasts each [1,2]. The milk given to them was spiked with a radioactive calcium tracer, similar to that of the iron, to understand if the phthalate compounds in the oats interfered with dietary uptake of calcium from the milk. The calcium tracer study showed that absorption of a sufficient amount of calcium would not be significantly affected by the phthalates in the oats. The final experiment involved nine students who had radioactive calcium injected directly into their bloodstream to serve as a baseline for how calcium is absorbed in the body without any interference from food or digestion [2].

“Instead of being taught, we were being used, and I don’t think that was right”

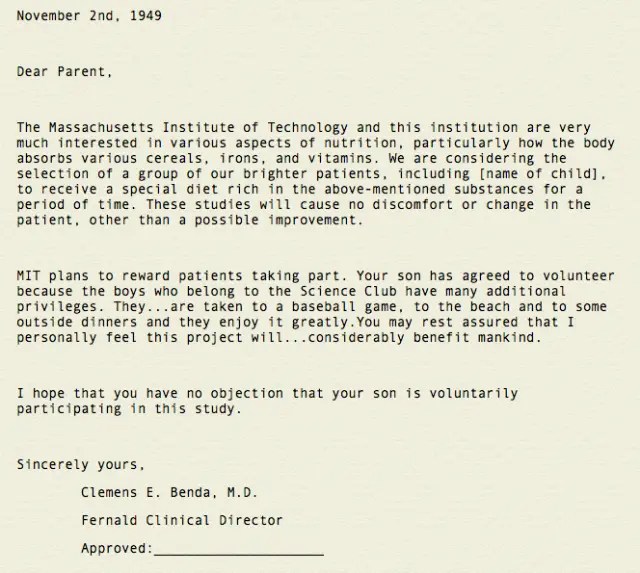

The research done by MIT for this study was very well controlled, researched, and executed from a scientific rigor standpoint [1,2]. Therefore, the studies are still considered major scientific discoveries. However, serious ethical issues underlie these ground-breaking studies [5,7]. Due to the state of the Fernald School, operating as a corrupt, underfunded, and apathetic institution, the boys living there were easy targets, vulnerable to coercion with food and fun and ill-equipped to question the studies that would be done at MIT. The parents were not informed either, and were not in a position to intervene. Most of the boys participating in the study were wards of the state2 , therefore the state, not the parents, were their legal guardians. In addition to this, informed consent laws to protect human research subjects did not exist at this time, especially for disabled individuals [7,10]. Consequently, informed consent was not provided to the participants or any living parents. The superintendent of the Fernald School was able to make medical decisions on behalf of the students [5].

Nevertheless, the school did provide parents with two very deceptive letters, which briefly explained what their child would be participating in, but did not ask for approval. These letters did not give any details of the study, did not mention experiments with radioactivity, nor did they state the possible risks associated with their child’s participation [11]. These letters further alluded that consent from the parent was accepted unless otherwise stated, in an effort to protect the school from any accusations of wrong-doing. Although unethical,these experiments were perfectly legal at that time, due to the lack of modern-day ethical and medical guidelines 3 [7,10]. Interestingly, the researchers conducting this study claimed that disabled children consumed larger amounts of cereal than the average juvenile, to justify their choice to use the boys from Fernald [1,11].

“Some of us had to sign our own forms, but at that particular time I could not read or write. I had no knowledge of anything other than the fact that I do what I’m told when I’m told.”

– Austin LaRoque, Fernald State School Student

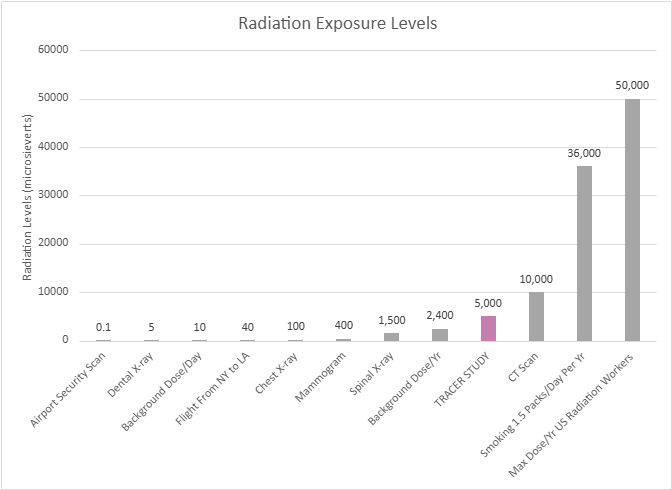

In 1993, almost 40 years after the conclusion of the tracer studies, MIT employed a task force to follow up on the research participants and determine if there were any lasting effects [3]. During the time of participation, the boys involved in the studies experienced levels of radiation equivalent to 50 chest x-rays [3,8]. Luckily, no severe effects were found. It is now known that the amount of radiation the boys experienced was less than current legal regulations. While participants didn’t experience any health complications, their safety had been jeopardized without their knowledge or their parents’. Therefore, the MIT task force suggested, “…all participants who were involved in human subject research which used radioactive materials at Massachusetts-operated facilities for persons with mental retardation should be compensated for any and all damage incurred as a result of such research” [4,9].

MIT chose not to act upon the task force’s suggestion until 1997, when a class action lawsuit for $60 million was filed against MIT and Quaker Oats by study participants and their families, arguing it was a violation of their civil rights. Both MIT and Quaker Oats agreed on a settlement of $1.85 million to each participant to “avoid the expense and diversion of a lengthy legal battle” [4,9]. In addition, MIT’s research director, Dr. Bertran Brill stated, “I admit they shouldn’t have focused on a population that was so captive and had no alternative. That was wrong” [9]. With this statement, the students at Fernald State School were finally indemnified for what had been done to them as children.

Unfortunately, this is not the only time vulnerable groups were targeted for scientific experimentation. From disabled boys, to prisoners, to minority and economically troubled groups, targeting powerless individuals is a shameful trend in the history of science. Even if the studies themselves are scientifically sound, acknowledging the unethical decisions surrounding these studies is very important . Respecting the human rights of all individuals is far more important than any scientific discovery. It is essential that we learn from our past, so that the next generation of scientists will never allow exploitation such as this to happen again.

- DISCLAIMER | This study in no way reflects the current ethical decisions of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Quaker Oats, or any associated studies. ↩︎

- A juvenile or incapacitated adult placed under the care of the government due to orphancy, abandonment, or inability to care for the child or for oneself ↩︎

- 1947 – Nuremberg Code introduced the ides of voluntary informed consent (not U.S. law, but influenced enactment)

1964/1975 – Declaration of Helsinki created to serve as the international ethics code for medical research, requiring informed consent, independent review, and protection of vulnerable groups (not binding U.S. law but heavily shaped it)

1974 – National Research Act was passed in the U.S. and served to require Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) ethics committees and protect people in federally funded research

1979 – Belmont Report passed as a foundational ethics document explaining respect for persons/informed consent, beneficence to minimize harm, and justice to ensure fair subject selection, explaining why the laws should exist

1991/2018 Revision – Common Rule for Federal Policy for Human Subjects Protection is the core rule that requires informed consent with full explanation of risk, IRB approval, and gives further protection to children, prisoners, pregnant persons, and people with impaired-decision making, allowing for the monitoring of ongoing studies and ability to withdraw at any time ↩︎

REFERENCES

1 | Boissoneault, L. (2017, March 8). A Spoonful of Sugar Helps the Radioactive Oatmeal Go Down. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/spoonful-sugar-helps-radioactive-oatmeal-go-down-180962424/

2 | Bronner, F., Harris, R. S., Maletskos, C.J., & Benda, C. E. (1956). Studies in Calcium Metabolism; the Fate of Intravenously Injected Radiocalcium in Human Beings. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 35(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI103254

3 | Campbell, K. D. (1994, May 11). Task Force Finds Fernald Research had no Significant Health Effects. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://news.mit.edu/1994/fernald-0511

4 | Court Approves Fernald Settlement. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (1998, January 7). https://news.mit.edu/1998/fernald-0107

5 | Crockett, Z. (2022, March 20). The Dark Secret of the MIT Science Club for Children. Priceonomics. https://priceonomics.com/the-mit-science-club-for-disabled-children/

6 | Daly, M. E. (n.d.). History of the Walter E. Fernald Development Center. https://www.city.waltham.ma.us/sites/g/files/vyhlif12301/f/file/file/fernald_center_history.pdf

7 | Denny, S. (n.d.). Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments Final Report. US Department Of Energy. https://ehss.energy.gov/ohre/roadmap/achre/chap7_5.html

8 | McCandless, D., & Hancock, M. (2013, August). Radiation Dosage Chart. Information is Beautiful. https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/radiation-dosage-chart/

9 | MIT Announces Settlement of Fernald Nutrition Studies Suit. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (1997, December 30). https://news.mit.edu/1997/fernald

10 | Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP). (2026, January 15). Federal policy for the Protection of Human Subjects ‘Common Rule. HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/common-rule/index.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

11 | Sharav, V. (2016, April 20). MIT reviews Fernald nutrition studies; Vest expresses concern. MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. https://ahrp.org/1944-1956-radioactive-nutrition-experiments-conducted-by-harvard-and-mit-on-disabled-children/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

12 | West, D. (1998, January). Radiation experiments on children at the Fernald and wrentham schools: Lessons for protocols in human subject research. Accountability in research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11660586/

IMAGE REFERENCES

1 | Digital Collections – University at Buffalo Libraries. (1901). Advertisement for Quaker oats [Photograph]. Public Domain. Retrieved from https://digital.lib.buffalo.edu/items/show/95016

2 | Fernald State School and Hospital. (Date Unknown). North Building — Historic images and photo gallery. Public Domain. Retrieved from https://fernaldstateschool.com/buildings/north

3 | Human Eugenics Records Archive. (1922). Photograph of Fernald boys in nutrition experiments. Public Domain. Retrieved from http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/864.html

4 | Crockett, Z. (1949, 2016). The Dark Secret of the MIT Science Club for Disabled Children [Letter reproduced]. Priceonomics. Public Domain. Retrieved from https://priceonomics.com/the-mit-science-club-for-disabled-children/

5 | Self-Produced. (2026). Information Retrieved from https://informationisbeautiful.net/visualizations/radiation-dosage-chart/