By Jmjosh90 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83933420

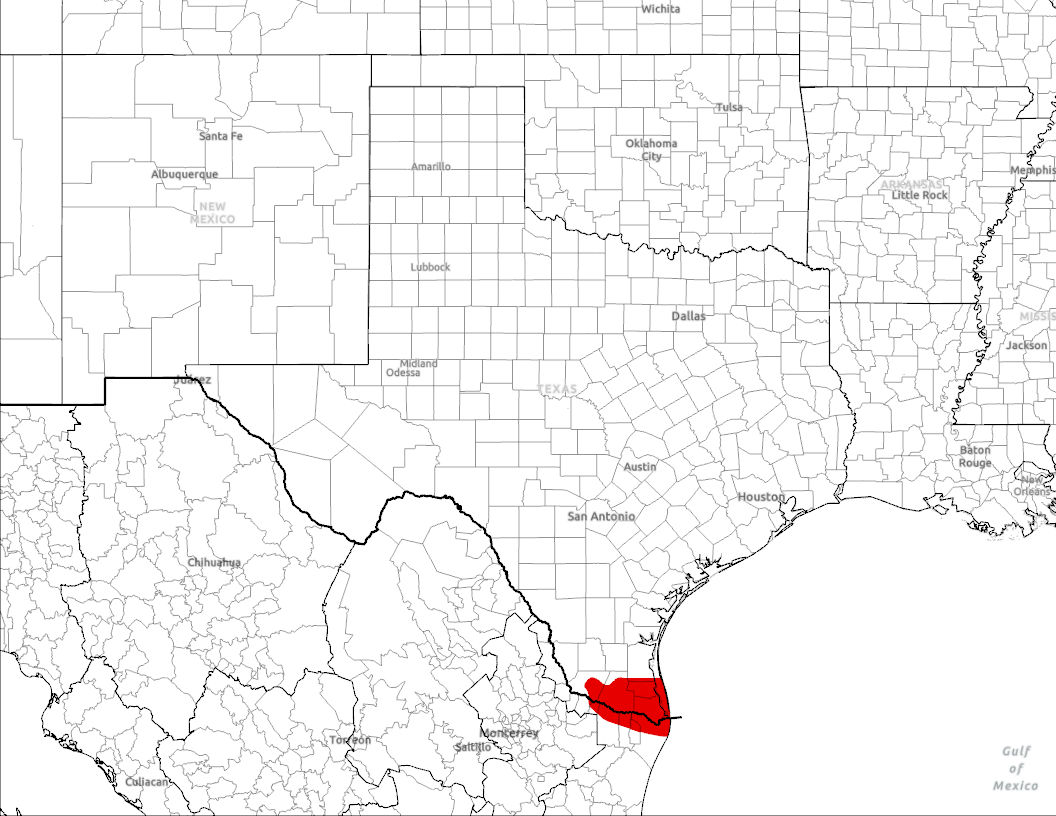

At the southernmost tip of Texas, there is a sunny and humid area called the Rio Grande Valley (aka the Valley), which is made up of Starr, Hidalgo, Willacy, and Cameron counties. Originally, the Valley was a prosperous agricultural center in the 1970s due to irrigation and railroads.1 Even today, South Padre Island brings many tourists and industry to the region to enjoy the Gulf of Mexico. Hispanic Texans “play a crucial role in the region’s labor force,” making up approximately 90% of the population, with a 10% increase in population size over the last ten years.5

Unfortunately, in the past several decades, the poverty rates began to climb, and the Valley is now “the poorest urban area in Texas.”1

It is the first day of my medical mission trip, and I am nervous but incredibly excited to work for a week in a free clinic in Harlingen, Texas, a mere 20 minutes from the US-Mexico border. There are 14 of us who flew in from around the country, including doctors, some graduate students, and mostly pre-health college students–each bringing a different skill set to our mission in the Valley. Most of us meet for the first time at the airport, and we spend the rest of the day in a state of jetlag, getting to know each other while unpacking, stocking up on food, and preparing our makeshift sleeping space in a small church across the street from the clinic. We go to bed, excited to meet Dr. Robinson and jump into our work the next morning.

It is 7:30 in the morning when we walk across the street to the clinic. I am surprised to see that there is already a line of ten people waiting for the clinic to open at 8 am. I notice that, despite the Valley’s large Hispanic population, the patients in line are a mix of several different ethnicities. The waiting patients are cheerful, chatting with each other and some saying hello to us as we head to the volunteer entrance. After meeting Dr. Robinson, he and two other volunteers give us a quick tour of the moderately-sized clinic. I was expecting a small doctor’s office, with a few patient rooms and reception. However, I was surprised to see that, despite the narrow hallways and small rooms, the modest clinic was well-equipped with a lab, wound clinic, women’s health wing, ultrasound room, endoscopy room, and three or four general patient rooms, all tucked into the building in an orderly fashion.

Dr. Stephen Robinson, MD, founded the Culture of Life Ministries clinic in Harlingen, Texas, 14 years ago. Wanting to do something about prevalent chronic health conditions like diabetes in the Valley, Dr. Robinson started the clinic as a pop-up out of his car. The pop-up has since bloomed into a freestanding clinic in what was formerly an old law firm. As their website states, the clinic provides “free health services” to all in need and provides a comprehensive list of the services they can provide, from ultrasounds to endoscopies. The clinic runs entirely on the goodwill of private donors and donations from any capable of giving that are placed in the small collection box outside the front door.

The clinic is run by volunteers, and so many different visiting missions will come and work in the clinic throughout the year. Because of this, Dr. Robinson had no problem with efficiently organizing our large group into individual roles. I am stationed in the lab, aiding in blood draws and collecting specimens. Given the line of people waiting outside when we arrived, we had a steady stream of patients all morning. Despite working as fast as we could, the lab orders kept piling up, and we had to turn two people away from receiving bloodwork. Later in the morning, I was moved from the lab to do waiting-room hospitality. I watched in frustration as the administrator came into the waiting room and explained to the two patients why they could not be seen. I thought, “If only I had worked faster that morning,” and, “Why don’t we just squeeze them in??” But I realized that a high volume of patients is common at the clinic, and so they often have to turn away people who have been waiting all morning or afternoon.

There are many people who need access to affordable healthcare in the Valley. Several counties in the Valley are designated by the Bureau of Primary Health Care as Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs), also known as “healthcare deserts,” which are areas in which healthcare needs are not met, either due to inadequate access or due to a lack of quality provided care. These healthcare deserts are caused by many other factors. One partial cause of this in the Valley is the recent rapid population growth of the area, which has strained the healthcare resources available.2 Over the last ten years, there has been a significant increase in population size.5 Transportation is a huge issue among people in the Valley, with many families lacking reliable transportation to medical facilities. Due to the low income average in individuals and households, approximately one-third of the inhabitants are uninsured, and many providers in the area do not treat uninsured patients.3 While the uninsured could use the ER for routine medical visits without insurance, for the Hispanic majority in the area, this could potentially put undocumented family members at risk of deportation. Therefore, there is a lack of trust in the healthcare providers. The lack of access and lack of trust, when added to the other factors hindering healthcare access, lead to a population with very poor health. Obesity and diabetes rates in the Valley are higher than the Texas average and significantly higher than the national US average.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Valley also had a significantly higher number of COVID-19 fatalities compared to other Texas counties.1

Going into this trip, I was concerned about navigating language barriers. I didn’t know Spanish, and I knew a large part of the population did not speak English. While working in the lab, there were several times when we had to ask a translator on staff to explain a protocol to a patient. For example, there were several Spanish-speaking patients who did not know they were supposed to drink water before getting their blood drawn. Because they spoke little English and we spoke little Spanish, we had to ask Ernie, an administrator, to communicate this to ensure that the patient got the correct information. Beyond this, only one student in our volunteer group knew Spanish proficiently, and he was translating for most of our time in the clinic that week.

Language barriers are a frequently encountered barrier to providing healthcare in the Valley. Hispanic Texans “play a crucial role in the region’s labor force,” making up approximately 90% of the population.5 Even if a healthcare provider is relatively competent in Spanish, cultural communication barriers could erode the trust between provider and patient. For example, if a physician addresses a patient in the informal “tú” instead of the formal “usted” that is used as a sign of respect, this could lead the patient to feel belittled or not listened to.6 Thus, you have a strained doctor-patient relationship that could contribute to lower-quality patient care. To avoid this situation, many hospitals and clinics have taken the initiative to provide interpreters for Spanish and other languages. For example, the Harlingen clinic had many Spanish-speaking care providers, and all the doctors were fluent. Likewise, Driscoll Children’s Hospital in the Valley has several interpreters on staff, and it states on its website, “Understanding every aspect of medical care isn’t a luxury—it’s a right.”7

Looking back on my time in Harlingen, I had some very different expectations than what I found to be true. I went into the trip expecting to be working at a pop-up clinic and serving mostly first generation migrants, but I ended up in a well-stocked and established clinic, aiding middle to lower class patients who have lived in the area for decades or moved from another part of the United States. This challenged my assumptions about healthcare outreach and the type of person who needs free healthcare. With the rise in insurance costs and a lack of clinics in the area, many patients above the poverty line still regularly access care from free clinics.

References

1. Blackburn, C. C., & Sierra, L. A. (2021). Anti-immigrant rhetoric, deteriorating health access, and COVID-19 in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas. Health security, 19(S1), S-50.

2. U.S.-Mexico Border Region Communities. MHP Salud. (2024, April 1). https://mhpsalud.org/who-we-serve/us-mexico-border-region/#:~:text=Access%20to%20Care&text=Further%2C%20many%20of%20the%20counties,Bureau%20of%20Primary%20Health%20Care.&text=And%20even%20if%20more%20health,much%20as%20the%20entire%20state.&text=Long%20distances%2C%20transportation%20problems%20and,short%20of%20comparable%20national%20averages.&text=As%20a%20result%2C%20many%20residents,across%20the%20border%20in%20Mexico.&text=The%20close%20proximity%20enables%20residents,visited%20a%20doctor%20in%20Mexico.

3. Torres, S. (2018). Health Care Access in the Rio Grande Valley: The Specialty Care Challenge. Edinburg, Texas.

4. Castañeda, H. (2017). Is coverage enough? Persistent health disparities in marginalised Latino border communities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(12), 2003–2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1323448

5. Power of the purse: Contributions of Hispanic Americans in the Rio Grande Valley. American Immigration Council. (2024, October 8). https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/contributions-hispanic-americans-rio-grande-valley

6. Melo, M. A. (2011). Access to healthcare for “undocumented citizens” in the Rio Grande Valley (Order No. 1494854). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (875791587). http://libproxy.clemson.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/access-healthcare-undocumented-citizens-rio/docview/875791587/se-27. Interpretation Services. Driscoll Children’s Hospital. (2024, January 23). https://driscollchildrens.org/patients/services/interpretation-services/