Prologue

The wail of a newborn broke the silence in the plain, crowded room. Dr. Kazue Togasaki finally smiled in relief and wiped sweat off her forehead. This was her second delivery of the day. Fatigue overwhelmed her, but the parents’ shining faces lifted her remaining strength.

As Dr. Togasaki stepped outside, it was not into the busy streets of San Francisco that she was used to. Instead, a desert wind pushed forcefully into her face. Watchtowers with armed guards stood beyond a few logging camps surrounded by barbed wire.

The towers cast their shadows over the camps, reminding the people there that this was not their home, but Manzanar, one of many Japanese concentration camps built on the soil of the United States.

This was a place where freedom was fenced, and human rights were transgressed.

I had the head nurse and the instructor of nurses at Stanford University Hospital and a doctor, all Japanese, working with me at Tanforan [A temporary detention center located in San Francisco for relocating internees to further remote areas.] — Dr. Togasaki [3].

Childhood and Early Years

You might wonder how Dr. Kazue Togasaki, an American citizen and physician, could end up detained and working in a concentration camp. To answer this, we must begin decades earlier. Dr. Kazue Togasaki was born in San Francisco in 1897 to Japanese immigrant parents [1]. Her father, Kikumatsu Togasaki, who first studied law in Japan, came to the US intending to pursue law in America.

However, social barriers prohibited Kikumatsu from practicing law in the United States. Fortunately, after staying in the US for a while, he met a wonderful woman named Shige Kushida, and they later married in Japan. Then, the couple moved back to the US and chose to pursue a small business.

Even though Kikumatsu Togasaki still thought of himself as a lawyer at heart, Shige, raised in a merchant family, taught him how to run a shop. Dr. Kazue Togasaki recalled, “My parents had a little store at 405 Geary that sold Japanese tea and rice and chinaware…Mother was the daughter of a merchant, so she knew how to buy and sell, but my father, a lawyer, not a businessman…” [3]. Over the years, their family grew to nine children; Dr. Togsaki was the second child and the eldest daughter [3].

Despite being born in the US, Dr. Togasaki did not grow up with the same schooling as many “Caucasian” children. In 1906, the city of San Francisco confirmed the “Exclusion Act” that segregated Japanese children to the “Oriental School.”

Dr. Togasaki was moved from school to school more than once [4]. She said, “The first I knew of discrimination was in 1908 when I was caught in the Exclusion Act” [10]. In the same year of 1906, when Kazue Togasaki was nine, catastrophe struck: One of the most devastating earthquakes in California history killed more than 3,000 people, torching the whole city of San Francisco [5].

I remember we got dressed and walked from our house to the 14th and Church, where there was a hill, and that afternoon and for two days in the daytime we sat, watching the city burn. — Dr. Togasaki [3].

The 1906 California Earthquake changed Dr. Togasaki’s life as a young girl. She saw the terror of the disaster, but she also saw humanity shine through the lens of medicine. Her parents were devout Christians, and after the earthquake, they turned their Japanese church into a makeshift hospital.

Dr. Kazue Togasaki helped translate Japanese to English for her “patients,” and cared for the wounded along with her mother. She gained first-hand experience in patient care, and the seed of her medical career was planted.

College and Medical School

With the ambition of practicing medicine, Dr. Kazue Togasaki started her academic journey. However, it was not a straight path. During that time, women were still looked down on for attending college, and higher education was seen as men’s business. Asian women were even more prejudiced by society.

Still, Dr. Kazue Togasaki did not let discrimination smother her dream. She first attended Stanford University and earned a bachelor’s degree in Zoology in January 1920. Initially, she planned to become a nurse, so she went on and attended the Children’s Hospital of Nursing and received her Registered Nurse (RN) degree in 1924. While this could have been the time for a young, ambitious Japanese nurse to serve her community, discrimination against women and Japanese Americans stopped her from practicing.

Dr. Togasaki recalled, “They had accepted me in the program, but I still couldn’t work here — the climate in San Francisco was that they just ‘didn’t use’ Japanese nurses; the staff wouldn’t have it.” [3]. Thinking that other related fields might be more welcoming for minorities, she obtained a Public Health degree from the University of California in 1927 [3], and succeeded in working several jobs from 1927 to 1929.

However, what Dr. Togasaki really desired was to work more directly with patients. With the encouragement from her parents, Dr. Kazue Togasaki applied to several medical schools throughout the US. Many medical schools in the 1920s – 1930s still held severe sexist and racist views, so she faced huge difficulties when applying.

Finally, one school broke the norm and accepted her — The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania. At last, Dr. Kazue Togasaki had the chance to study medicine and became a doctor [7, 20]. Dr. Kazue Togasaki graduated from The Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1933 and became one of the earliest Japanese-American women to earn an MD degree in the US.

WWII Breaks out

Dr. Togasaki returned to San Francisco and opened a clinic for Japanese patients. She was in the happiest moments of her life, having finally achieved her dream of serving her people as a doctor.

Then, World War II broke out. Warfare in Europe eventually spread worldwide. Making things worse, Japan sided with the Axis Powers along with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Inevitably, tension between Japan and the US began to build.

On a peaceful Sunday morning on December 7th, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, starting the war between Japan and the US. This war immediately put Japanese Americans in a difficult position [8]. Many Japanese Americans feared for their future; their loyalty was questioned by people around them and by the US government.

On February 19th, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering the US Army to “remove” all people of Japanese descent to concentration camps on the West Coast, regardless of birth and citizenship.

Within four months, 110,000 people were forced to leave their warm homes and relocate to the freezing California desert [9]. While Dr. Togasaki was running her clinic as an obstetrician, news of the Executive Order hit. She had to abandon her clinic with many of her family members and report to Tanforan.

The concentration camp was officially named the Tanforan Assembly Center. It was a temporary detention facility for Japanese Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area, and was operated by the U.S. Army under director Frank L. Davis. Nearly 8,000 people, the majority of them born in the US, were sent to the Tanforan facility, where they waited to be sent to more remote camps.

Many people could not believe that concentration camps similar to those in Europe were now operating on US soil. People feared for their fate in the unknown future.

The relocation was war hysteria. They had just told us, on such and such a day be ready to leave. They had big buses and you were allowed to take two suitcases, whatever you could carry. — Dr. Togasaki [3].

To no one’s surprise, this sudden Executive Order had no real preparation for moving such a large population in a short time. The concentration camps often failed to meet basic needs, as they were located in remote areas with limited supplies. Moreover, the government did not plan to spend any wartime resources on these potential American-born “traitors.”

When people first arrived at the camp, they were asked to pledge loyalty at the front gate of the camp with Army soldiers beside them. Then people were crammed into overcrowded barracks built from uninsulated plywood and tar paper. The harsh winter desert weather distressed its new residents, as the Army guards patrolled the camps behind barbed wire on high watchtowers [11].

To minimize the cost of the camps, only inexpensive foods were supplied to the internees. People were fed on wieners, macaroni, pickled vegetables, and starch. Fresh meat and milk were always in short supply [22]. These poor conditions alarmed many doctors about the risk of epidemic disease outbreaks. Yet, despite the suggestion to provide vaccinations before the mass relocation, fewer than 1% of internees had received a typhoid immunization before arrival.

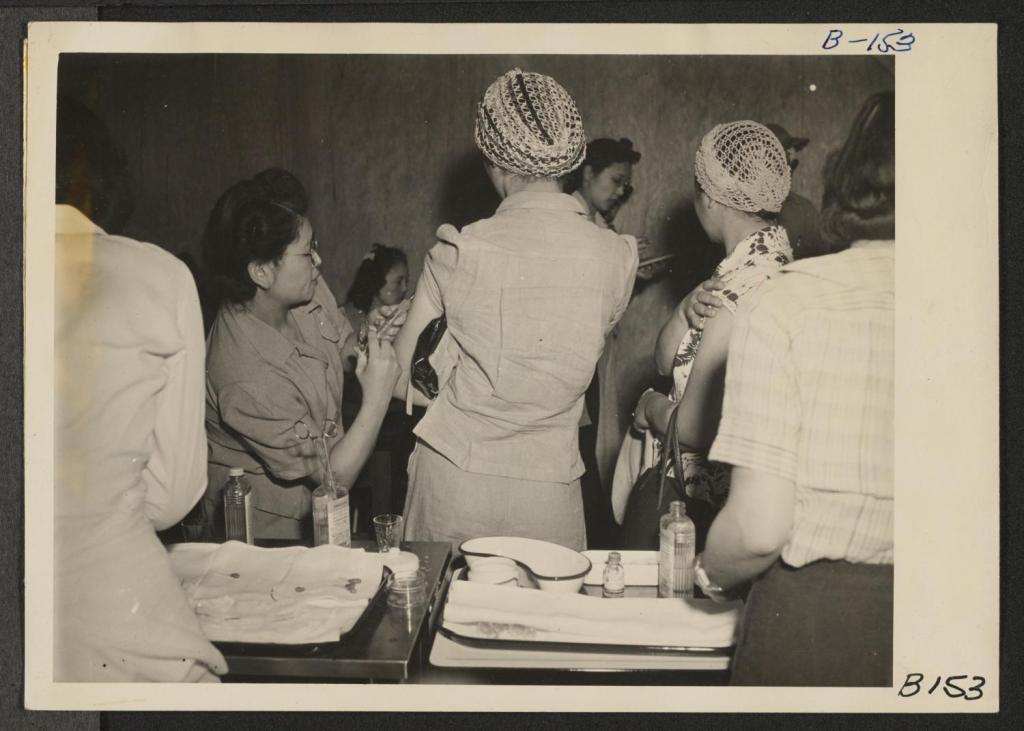

After receiving repeated concerns from Japanese physicians, the Public Health Department finally decided to deploy Japanese doctors from the camps to provide vaccinations and health screenings. Dr. Kazue Togasaki was one of the Japanese doctors.

When Dr. Togasaki received the order to treat patients in Tanforan Internment Center, she immediately assembled a healthcare team of Japanese doctors and nurses. She even asked to tear off a door so it could be used for delivering babies.

Dr. Togasaki vaccinated new internees, led hygiene inspections, trained healthcare workers at the scene, and went from camp to camp to treat more patients. One report described the conditions when Dr. Togasaki first arrived: “Inmate Dr. Kazue Togasaki lamented the fact that despite the contamination, there was no chlorination available” [13].

The situation in the camps was poor, but everyone worked to improve them. Records show Dr. Togasaki delivered 50 babies in one month alone [9,12]. Because of her compassion and integrity in serving her community under difficult conditions, she was later deployed at six other camps, including Stockton, Tule, Poston, Manzanar, and Topaz. In one of America’s darkest times, we also saw the brightest side of humanity from people like Dr. Kazue Togasaki.

In that month, I delivered 50 babies in the camp. Sometimes I stood behind the doctor and taught him how to deliver. I thought it was my duty. — Dr. Togasaki [3].

Aftermath of World War II

Dr. Togasaki continued to serve her people and her nation until the end of the war despite the unlawful treatment. When Dr. Togasaki and her family were finally released from the concentration camps, what awaited them was not the warm house they had left behind. Like many Japanese people, when they returned to their home in San Francisco, they found it fully ransacked, with nothing valuable left but a chaotic mess.

During the war, it was common for opportunists to burglarize and vandalize homes owned by Japanese Americans and take anything inside as their own. This chaos did not stop Dr. Togasaki from rebuilding her life. She opened a clinic in her neighborhood and became the only Japanese woman practicing medicine in that region [3].

The community was glad to see Dr. Togasaki back home, and her good work earned her a strong reputation among patients of all races. She continued to dedicate her life to obstetrics and gynecology, often caring for underserved patients at no charge, helping unmarried mothers deliver their babies, and housing Japanese immigrants in her own home [1,16].

Despite being mistrusted and mistreated by society throughout her life, Dr. Togasaki treated patients regardless of whether they were American or Japanese, because she saw them equally as human. As a victim of racial and sexist discrimination, Dr. Togasaki is an example for all of us to stop discrimination.

By the time she retired at 75, she had delivered thousands of babies in her whole medical career! After retirement, Dr. Togasaki’s health declined; she fought Alzheimer’s disease and passed away at the ripe age of 95 on December 15, 1992, well-loved by her family and the neighborhood [15,17].

I grew up on Post and Buchanan. What was there is all gone now, but, you see, it’s still near where I grew up. — Dr. Togasaki [3].

References:

- Ware, S. (2004). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century. United Kingdom: Belknap Press.

- Kazue Togasaki interview on her life in Japanese American relocation centers and her medical career conducted by Sandra Waugh and Eric Leong for the Combined Asian American Resources Project, 1974 may 4. Audio: Kazue Togasaki interview on her life in Japanese American relocation centers and her medical career conducted by Sandra Waugh and Eric Leong for the Combined Asian American Resources Project, 1974 May 4. (n.d.). https://avplayer.lib.berkeley.edu/Audio-Public-CAVPP/(cavpp)cubanc_000329

- Pioneering Japanese-American doctor remembers Quake, World War II, her neighborhoods. (n.d.). https://hoodline.com/2015/08/kazue-togasaki-quake-world-war-neighborhoods/

- Segregation of Japanese School Kids in San Francisco sparks an international incident – celebrate California. (n.d.). https://celebratecalifornia.library.ca.gov/japanese-segregation/

- Casualties and damage after the 1906 earthquake. U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/events/1906calif/18april/casualties.php

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Dr. Kazue Togasaki (U.S. National Park Service). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/dr-kazuetogasaki.htm

- Admin-Flintriver. (2023, June 8). Dr kazue togasaki. IYASU Vegan Medical Bags. https://iyasubags.com/dr-kazue-togasaki/

- Pearl Harbor Attack. (n.d.). https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1941/pearl-harbor.html

- Nakayama, D. K., & Jensen, G. M. (2011). Professionalism behind barbed wire: health care in World War II Japanese-American concentration camps. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(4), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30317-5

- McGOWAN, M. J. (1955, February 28). WOMAN gives view: lessening of race problems told. The San Francisco Examiner.

- Our past, their present Japanese internment at Topaz. (n.d.). https://history.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/K12_Japanese-Internment-at-Topaz_OPTP.pdf

- Yuko, E. (n.d.). America has a long history of pitting politics against Public Health | Bitch Media. Bitchmedia. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/american-has-long-history-pitting-politics-against-public-health

- Manzanar | Densho Encyclopedia. (n.d.-a). https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Manzanar/

- National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). National Archives and Records Administration. https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=3099&mtch=13&tf=F&q=Togasaki&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=92515&rlst=92518%2C92511%2C92512%2C92513%2C92514%2C92515%2C92516%2C92517%2C92519%2C92520

- Dr Kazue Togasaki (1897-1992) – find a grave… Find a Grave. (n.d.). https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/87599108/kazue-togasaki

- Author, Hang Loi, Loi, H., In her 34 years at 3M Company, & posts, V. all. (2025, July 17). Remarkable Asian Pacific American Women in STEM – APAHM. All Together. https://alltogether.swe.org/2023/05/apahm-2023-remarkable-asian-pacific-american-women-in-stem/

- 1992 obituary for Kazue Togasaki (starts at bottom of column). Newspapers.com. (1992, December 22). https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner-1992-obituary/102414379/

- Mission & History. Tsuru for Solidarity. (2023, December 28). https://tsuruforsolidarity.org/mission-history/

- Lei, C. (2025, February 18). Bay Area Japanese Americans draw on WWII trauma to resist deportation threats. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/news/12021919/bay-area-japanese-americans-draw-on-wwii-trauma-resist-deportation-threats

- Journal of the American Medical Association. (1889). United States: American Medical Association.

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). National Park Service: Confinement and ethnicity (Chapter 16). National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16m.htm

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Families, food, and dining. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/miin/learn/historyculture/families-food-and-dining.htm

Image Sources:

- Miyatake, TM. 1942, Guard Tower 4, Manzanar. Toyo Miyatake Studio. https://www.nps.gov/places/manzanar-icon-of-confinement.htm

- Lawrence, GRL. 1906. Fire in San Francisco following the great earthquake of 1906. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/04/photos-of-the-1906-san-francisco-earthquake/477750/

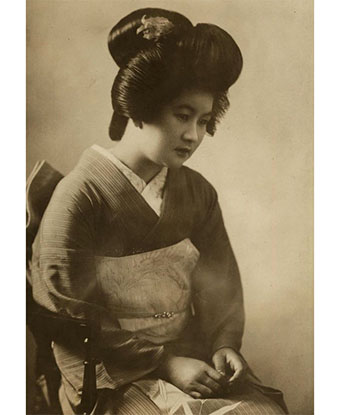

- Author unknown. 1933. Kazue Togasaki graduated from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1933. Drexel University Libraries: Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania Photograph Collection. https://drexel.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=01DRXU_INST:01DRXU&tab=Everything&docid=alma991015136539204721

- Lange, DL. 1942. Ten cars of evacuees of Japanese ancestry are now aboard and the doors are closed. Their Caucasian friends and the staff of the Wartime Civil Control Administration stations are watching the departure from the platform. Evacuees are leaving their homes and ranches, in a rich agricultural district, bound for Merced Assembly Center about 125 miles away. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. https://anchoreditions.com/blog/dorothea-lange-censored-photographs

- Clem, AC. 1942. Newcomers are vaccinated by evacuee nurses and doctors upon arrival at War Relocation Authority centers for evacuees of Japanese ancestry. Online Archive of California. https://oac4.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft5199n8w8/?order=1&brand=oac4

- Limjoco, LL. 1978. Dr. Togasaki during this 1978 Study Center interview. Central City Extra. https://studycenter.org/project/filmore-2/

- Ortiz, SO. 2012. A sentry tower, one of the only original structures from Manzanar Internment Camp left standing after the site was dismantled upon its closure. https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/76000484