By Lillian Mergen

It is the stem cell’s ability to become any other type of cell that makes it unique, controversial, and full of opportunity – The Mayo Clinic

Imagine you are a painter. In front of you, there is a blank canvas and all the materials and skills you need to create something new. What would you create?

Now, imagine yourself to be a scientist. Your canvas is now a stem cell. Your materials are the genetic machinery, and your skills are technologies like molecular cloning and gene editing. Your “something new” has become a treatment for a debilitating disease.

Cells are the basic building blocks of the body. Stem cells are the most fundamental version of a cell – they are the cell type from which all other cell types arise. When a stem cell divides, the two new cells are called daughter cells, which can either remain as a stem cell or they can change (i.e. “differentiate”), into new cell types. As a baby grows in its mother’s womb, the daughter stem cells will differentiate into every specific type of cell found in the body, like blood, brain, or muscle cells. Starting from a single fertilized egg, stem cells eventually form all 1,250,000,000,000 cells in the newborn.1

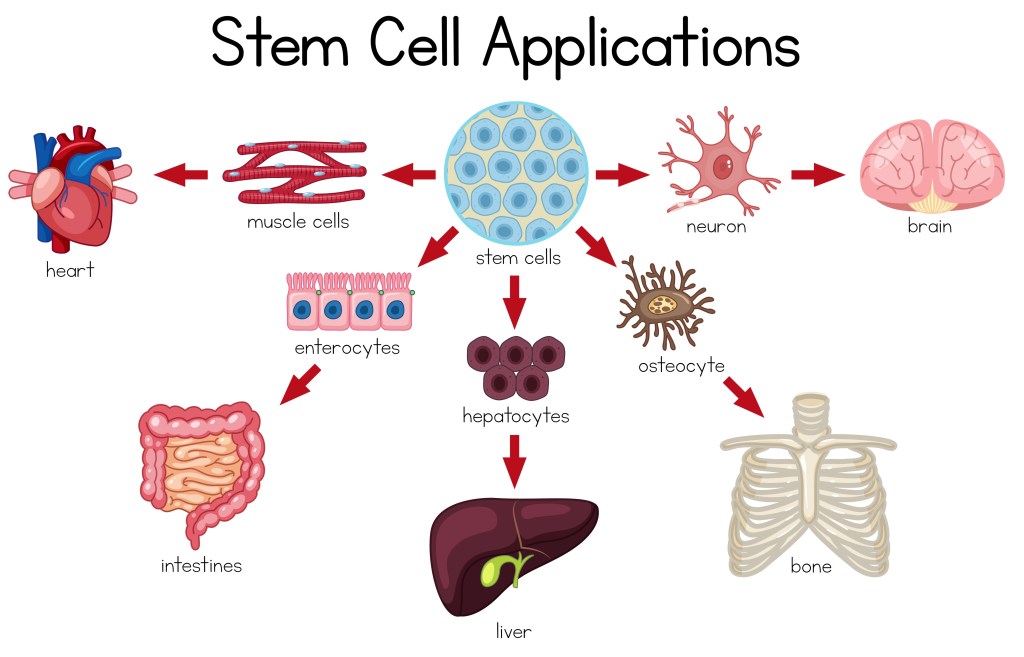

There is a lot of controversy regarding stem cells, mostly surrounding the use of embryonic stem cells. According to the Mayo Clinic, human embryonic stem cells are isolated during one of the earliest stages of embryonic growth, when they are around three to five days old and consist of approximately 150 cells.2 Embryonic stem cells are categorized as “pluripotent” stem cells (see details below), which are the stem cell type that can become nearly any other type of cell, making them extremely versatile.2 The opportunity that stem cells represent is that if you can program them to become other cells, you could replace cancerous bone marrow, grow new skin for burn victims, create a working pancreas for diabetics, and cure genetic diseases.

In order to create a new pancreas or replace bone marrow, research must be conducted on stem cells. To work with stem cells, they need to be developed into stem cell lines, which are groups of stem cells that are grown from the same original cell, and therefore are identical.4 Once a stem cell line is established, the stem cells can be grown in relatively large quantities, frozen for storage, and shared with the scientific research community.4

So, you may be wondering, how many stem cell lines are there now? As of this writing, there are about 400 human embryonic stem cell lines that are approved to be used in the US for biomedical research.6 This number of stem cell lines is much higher than during the period between 2001 and 2008.6 In 2001, a bill was passed that limited scientists to using only the 60 stem cell lines that were in existence at that time, with only 21 of them being viable.6

Totipotent – The most powerful type of stem cell, as they can differentiate into any cell type. They are found during the very beginning of embryonic development at the 2-4 cell stage. When they divide, they produce pluripotent stem cells.3

Pluripotent – This type of stem cell is slightly less “powerful” than totipotent stem cells, as they are restricted to becoming cells that form the three different germ layers in the embryo: the ectoderm, the mesoderm, and the endoderm. When they divide, they produce multipotent stem cells.3

Multipotent – This type of stem cell is the most restricted. These are committed to making cells from only one of the three germ layers. They can still develop into numerous types of cells, but the cells are all part of the same germ layer. When they divide, they produce the specialized cell types that we think of in our body, such as cardiac muscle cells or bone cells.3

What happened with stem cells in August of 2001?

In August 2001, President George W. Bush announced that federal funding would only be available for research on stem cells that had already been isolated and turned into stem cell lines.7 Bush further stated that moving forward, the destruction of human embryos and the development of new stem cell lines would not be supported by the federal government and its funds.7 In his announcement, President Bush said, “I have concluded that we should allow federal funds to be used for research on these existing stem cell lines, where the life or death decision has already been made.”7 He further described his decision as a compromise, in that taxpayers would support stem cell research while not drifting further into questions of morality involving the human embryo.7

In enacting this stem cell policy, President Bush did two things. First, he set a precedent that the federal government can hold an opinion on the morality, or ethical responsibility regarding embryonic stem cells.8 Second, he set a precedent at the same time that the federal government supported stem cell research and recognized its potential benefits.8 As a result of President Bush’s decision, all federally funded stem cell research was immediately limited to the 60 stem cells lines that already existed at that time.6

The new policy and resulting cuts in federal funding were not popular amongst most researchers. The stem cell ban led to many embryonic stem cell researchers laboriously separating their research environments based on whether or not the “staff, equipment, and lab space” was paid for via federal or private funding.9 Embryonic stem cell researchers who had been working with international researchers had their collaborations stifled due to the funding cuts and work limitations.9 The elite universities, which had more significant economic resources, were able to bounce back from the initial ban much faster than lower-tier and/or less endowed universities.9 The wealthier universities were able to develop alternative funding mechanisms to continue their contributions to human embryonic stem cell research.10

The scientific and technical limitations of the few stem cells lines approved for use aggravated many embryonic stem cell researchers. The approved stem cell lines were not incredibly diverse, either genetically or ethnically.9 This meant that certain diseases with a strong genetic component such as Parkinson’s “… could no longer be studied in embryonic stem cells.”9 The existing stem cell lines also were limited to certain ethnicities (primarily White, North American or European), which left “… uncertainty with regard to cellular processes in minority groups.”9

The scientific community responds strategically to the institutional and policy conditions affecting science.10

In 2006, researchers at Kyoto University, Drs. Kazutoshi Takahashi and Shinya Yamanaka developed the first successful method to make pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse skin cells.11 The Kyoto researchers did this by “de-differentiating” adult stem cells, reverting them back to an embryonic state, thus restoring pluripotency.11 Takahashi and Yamanaka figured out the exact combination of genes to turn on and off to make the cells “forget” they were skin cells, resetting them to the pluripotent stem cell identity.11 This innovation started with mouse cells, but the human version of these induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPS cells, were produced at the same university only one year later. In 2012, Dr. Yamanaka went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, along with Dr. John Gurdon of the University of Oxford.12

“Following the discovery, the White House noted that by ‘supporting alternative approaches, President Bush is encouraging scientific advancement within ethical Boundaries’. Subsequent U.S. progress in iPS cell research may have well enjoyed unique encouragement under Bush’s policies.”9

So, what are iPS cells and why are they so revolutionary?

iPS cells are normal adult cells, which are fully differentiated and specialized, that have been reverted back to their pluripotent state.13 Human iPS cell technology offers many advantages: they are pluripotent, created from human adult cells, and are highly accessible.13 The development of iPS cells has opened the door to numerous possibilities for scientists when it comes to disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine.14 To date, iPS cells have been used for modeling human disease, and for assessing the efficiency and potential toxicity of different drugs.14 Most exciting is that iPS cell technology enables the ability to create patient-specific treatments using pluripotent stem cells created from the patients’ own cells.14

Finally, I want you to think back to that blank canvas. Embryonic stem cells are the blank canvas that can become just about anything with the right tools. With iPS cells, you can take an already finished painting and do something new. You can paint the canvas white and start over again to paint the right picture, a better picture, a new picture of health.

© kaneez / Adobe Stock (AI generated Image)

Works Cited

1. Number of cells in newborn infant. Number of cells in newborn infant – Human Homo sapiens – BNID 106413. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?id=106413&ver=4.

2. Answers to your questions about Stem Cell Research. Mayo Clinic. March 23, 2024. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/bone-marrow-transplant/in-depth/stem-cells/art-20048117.

3. Facebook.com/bioinformantworldwide. Do you know the 5 types of stem cells? BioInformant. March 9, 2024. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://bioinformant.com/types-of-stem-cells/#:~:text=Totipotent%20(or%20Omnipotent)%20Stem%20Cells,Oligopotent%20Stem%20Cells.

4. Creating new types of stem cells. CIRM. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.cirm.ca.gov/creating-new-types-stem-cells/.

6. Ludwig TE, Kujak A, Rauti A, et al. 20 years of human pluripotent stem cell research: It all started with five lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(5):644-648. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.009

7. Seelye KQ. Bush gives his backing for limited research on existing stem cells. The New York Times. August 10, 2001. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/08/10/us/president-s-decision-overview-bush-gives-his-backing-for-limited-research.html.

8. The stem cell debate: Is it over? Learn.Genetics. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/stemcells/scissues#:~:text=But%20when%20.

9. Murugan V. Embryonic stem cell research: a decade of debate from Bush to Obama. Yale J Biol Med. 2009;82(3):101-103.

10. Furman JL, Murray F, Stern S. Growing stem cells: The impact of federal funding policy on the U.S. Scientific Frontier. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2012;31(3):661-705. doi:10.1002/pam.21644

11. Omole AE, Fakoya AO. Ten Years of progress and promise of induced pluripotent stem cells: Historical origins, characteristics, mechanisms, limitations, and potential applications. Published online October 26, 2017. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.3374v1

12. The nobel prize in physiology or medicine 2012. NobelPrize.org. Accessed May 6, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2012/press-release/.

13. Ye L, Swingen C, Zhang J. Induced pluripotent stem cells and their potential for basic and Clinical Sciences. Current Cardiology Reviews. 2013;9(1):63-72. doi:10.2174/1573403×11309010008 14. Mondal A, Talukdar A, Haque R. Unlocking the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells in revolutionizing cancer therapy. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2024;19. doi:10.2174/011574888×294791240408055222

Image Credits

“Embryonic stem cells colony under a microscope. Cellular therapy and research of regeneration and disease treatment in seamless 3D illustration. Biology and medicine of human body concept. 4K.” © Eduard Muzhevskyi / Adobe Stock

“Stem Cell Applications diagram” © brgfx / Adobe Stock

“Bush Stem Cells” AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

“Nobel Prize Yamanaka and Gurdon” The Yomiuri Shimbun via AP Images

“Moss Concrete Wall Background, Close up Dirty Cement Wall Texture,Old plaster surface old plastered wall wallpaper old,old damaged and dirty white wall with peeling paint – rough dirty texture” © kaneez / Adobe Stock (AI generated Image)