By Margaret Zendzian

1875-1896: Life Before Einstein

Everyone knows who Albert Einstein was, from his wacky tongue photo to his famous equation E=mc2. But were his achievements entirely his own? Opinion is divided on the history of Einstein’s work. Many say Mileva Marić, his lesser-known first wife, could have played a large role in his physics and mathematics papers. Others say she did not help and was just a housewife who took care of their children. However, you can’t deny Mileva’s intelligence: she was just as gifted as Albert, raising the question of whether her brilliance helped shape some of his greatest ideas.Mileva Marić was born in 1875 in Titel, Austria-Hungary, to an affluent family of Serbian descent. From a young age, she was a bright girl1. As a teenager, she was allowed to attend an all-boys school in Zagreb1. Throughout her education, she continued to excel in mathematics and physics1. Mileva’s father played an influential part in her continuing her educational journey, pushing her to travel to Switzerland to continue her studies1. After finishing her secondary studies in 1896, she enrolled at the University of Zurich, which was the first university in Central Europe to admit women as matriculated students (unlike Austrian and German universities, which didn’t do so until around the turn of the 20th century2). She briefly studied medicine before transferring to the Polytechnic Institute of Zurich to study mathematics and physics. However, it’s interesting to note that the official student statistics of the Polytechnic do not show any enrolled women before 19173. Therefore, women like Mileva were likely enlisted as Gasthörer– auditors- meaning much of their student life during this period was without academic credit.3

1896-1919: Life with Einstein

Both Mileva and Albert were admitted into the physics-mathematics section of the Polytechnic Institute of Zurich in 1896, and they soon became inseparable4. As a student, Mileva was meticulous in her studies, always organized and on top of everything, while Albert attended only a few lectures and was very disorganized4. During university, Mileva constantly helped Albert to channel his energy and guide his studies4.

From October 1897 to the following April, Mileva spent a semester abroad at Heidelberg University, where she audited mathematics and physics classes1. Upon arriving back at the Polytechnic Institute of Zurich, she took classes in differential and integral calculus, descriptive and projective geometry, mechanics, theoretical physics, applied physics, experimental physics, and astronomy3. In 1899, she took her intermediate diploma examinations, and her results placed her fifth out of the six students who took the exams that year. While her physics grades were the same as Albert’s, she scored higher than him in Applied Physics.3 A year later she took her final exam, but failed5,6. While many stories reiterate Mileva’s academic failure, very little is mentioned about the tutor who scored her exam5,6. Interestingly, all the other students in her small group (all male) obtained at least 5.5 in this subject. It was only Mileva who was assigned such a low grade5,6. At the time, Wilhelm Fiedler, a professor at Polytechnic who taught the geometry that comprised the Theory of Functions course, was also a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences5,6. Some members of that body felt there was no place for women in science, let alone physics, and Professor Fiedler may have shared that belief along with his colleagues 5,6.

During this time, Albert and Mileva had been working together on a research article on capillarity. On December 13, 1900, they submitted their paper titled “Conclusions Drawn from the Phenomena of Capillarity,” which explored the surface tensions between a liquid and its vapor using a phenomenological theory based on two-body forces between molecules7. However, only Albert’s name ended up on the submitted final draft. This erasure of Mileva’s contribution reflects a broader pattern of the era, in which women scientists were often denied recognition for their work due to prevailing societal and institutional biases. As the historical record shows, women were frequently barred from formal scientific education and excluded from publishing under their own names, leading to their discoveries being overlooked or attributed to their male colleagues8.

Albert’s family strongly opposed his relationship with Mileva. She was neither Jewish nor German, and she had a lifelong limp4. According to Albert’s mother, Mileva was far too intellectual. In a letter from Albert to Mileva dated July 27, 1900, he stated that his mother told him:

“By the time you’re 30, she’ll already be an old hag!” and “She cannot enter a respectable family”4

In the early spring of 1901, the two went on a vacation together to Lake Como in Italy4. There, Mileva’s destiny changed abruptly. She became pregnant, but Albert still refused to marry her.4 They left their lover’s retreat, and Mileva sat in for her second and final attempt on her diploma exam while three months pregnant9. Again, she did not pass her Theory of Functions examination, and her marks in Theoretical and Experimental Physics came in lower than her previous attempt.9 Mileva, pregnant and unmarried, was forced to abandon her studies and return to Serbia4. There, she gave birth to a girl in January of 1902.4 No one knows what happened to the baby after she was born, as there are no birth or death certificates.4 Some accounts suggest that the child died soon after contracting scarlet fever, while others believe she was put up for adoption.4

In June of 1902, Albert received a job offer at a patent office, and his father finally granted him permission to marry Mileva4. The two married on January 6, 1903 and they settled into life together: while Albert worked, Mileva assumed all the domestic duties4. However, during the evenings, the pair worked together on mathematics and physics. On May 14, 1904, their son Hans-Albert was born.4 In 1905- also known as Albert’s ‘miracle year’- the couple traveled to Serbia, where they met numerous of Mileva’s relatives and friends, who described how they collaborated together.4 Zarko Marić, a cousin of Mileva’s father, lived in the countryside property where the Einsteins stayed during their visit. He told Krstić (a former physics professor at Ljubljana University) how Mileva calculated, wrote, and worked with Albert.4 The couple often sat in the garden to discuss physics. Harmony and mutual respect prevailed. During an evening gathering of young intellectuals hosted by Mileva’s brother, Albert declared:

“I need my wife. She solves for me all my mathematical problems.”4

While working in the patent office, Albert also gave unpaid lectures in Bern until he was offered his first academic position in Zurich in 19094. At this time, documents show that Mileva was still assisting him. Eight pages of Albert’s first lecture notes are in her handwriting, as is a letter drafted in 1910 in reply to Max Planck, who had sought Albert’s opinion.4 As Albert’s groundbreaking papers began to gain significant recognition within the scientific community, his reputation grew rapidly, and he soon became a celebrated figure among physicists6. He traveled across Europe delivering lectures and enjoying the professional esteem that came with his rising prominence in the field. His recognition remained largely within academic circles until he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921. While Albert was traveling, Mileva stayed behind in Prague with their children to take care of them6. Mileva hated Prague and soon became depressed because she was no longer a part of the scientific community6. Albert started to resent Mileva’s demands for attention, as he was far too busy to occupy himself with family life. Further indicating Albert’s and Mileva’s estrangement: On a trip to Berlin in 1912, Albert became reacquainted with a cousin, Elsa Löwenthal, whom he had known as a child10. The two started a romantic correspondence, and in 1914, Albert moved to Berlin, where Elsa lived10.

1919-1948: Life after Einstein

After years of living apart, Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić officially divorced in 191911. Their marriage had been strained for years, marked by emotional distance and financial struggles. Albert moved forward with his personal life, marrying his cousin Elsa just months after the divorce was finalized. Mileva was left to care for their two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard, with only sporadic financial support from Albert4. Raising two sons alone was no easy task, especially as their younger son, Eduard, suffered from severe mental illness. He was later diagnosed with schizophrenia and required extensive care, placing an even greater financial strain on Mileva4. Mileva found herself in an increasingly difficult position, and the correspondence between Mileva and Albert reveals a relationship that had become transactional, with Mileva frequently writing to Albert about the inadequacy of the money he sent4. The only moments of warmth between them appeared when discussing their children, a rare shared concern amidst years of growing resentment. Despite her own struggles, Mileva remained devoted to her children, particularly Eduard, ensuring he received medical attention and support4. Meanwhile, Hans Albert pursued a career in engineering, eventually moving to the United States4.

Mileva’s later life was burdened by both financial and personal hardships. She lived a modest and often difficult life in Zurich, overshadowed by the immense fame of her former husband. She continued to rely on Albert’s financial assistance, but the payments often were inconsistent, leading to constant disputes. While Albert was celebrated as one of the greatest minds of the 20th century, Mileva’s contributions, both in the early years of his scientific work and in raising their children, remained largely unrecognized. She passed away in 1948, far from the spotlight that had once surrounded her, leaving behind a legacy that remains debated by historians and scholars to this day1.

Afterword: Did Mileva Contribute?

While Mileva Marić’s contributions to Albert’s work remain a matter of speculation, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that she was more than just a supportive wife. Mileva was a talented physicist and mathematician in her own right whose potential was stifled by societal norms and systemic biases. While Albert legally owed her financial compensation through their divorce, history may owe her something more: acknowledgment of the role she played in shaping one of the greatest scientific minds of the 20th century. I believe that Mileva truly did help Albert write some of his papers. However, because of the era in which she lived, Mileva didn’t get the credit she deserved.

Many continue to raise the question of whether Mileva deserves formal recognition for Albert’s work. Unfortunately, no official documents list her as a co-author, and there is no direct proof that she contributed substantial original ideas to his major theories. However, circumstantial evidence, including Albert’s own words and family accounts, suggests she played an essential role in his development as a scientist. Albert himself wrote to Mileva on March 27, 1901, strongly implying collaboration, stating:

“How happy and proud I will be when the two of us together will have brought our work on relative motion to a victorious conclusion.”4

Additional support for Mileva’s role in Albert’s research comes from modern gender bias research, which highlights a consistent pattern of women in research teams being significantly less likely than men to be credited with authorship12. One study found that women are 13.24% less likely to be named in academic articles and 58.40% less likely to be listed on patents produced by their teams12. The reasons for this underrepresentation include their work being overlooked, unappreciated, or ignored12. While direct data from the early 1900s is scarce, these trends suggest that Mileva’s contributions may have suffered the same fate, especially considering that she was one of the only women in her class studying physics and mathematics.

At the very least, Marić’s story underscores the broader issue of women’s erasure from scientific history. She was a gifted physicist who, under different circumstances, might have had her own distinguished career.

Sources

Mileva Einstein-Maric – Facts, Husband & Life. Biography. Published July 15, 2020. https://www.biography.com/history-culture/mileva-einstein-maric

Higher Education in Central Europe. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/higher-education-in-central-europe

Asmodelle E. The Collaboration of Mileva Maric and Albert Einstein. Published March 27, 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274263348_The_Collaboration_of_Mileva_Maric_and_Albert_Einstein

Gagnon P. The Forgotten Life of Einstein’s First Wife. Scientific American. Published December 19, 2016. https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/guest-blog/the-forgotten-life-of-einsteins-first-wife/

Stachel J., Cassidy D.C., & Schulmann R., The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1: The Early Years, 1879-1902, Princeton University Press, 1987.

Calaprice A. & Lipscombe T., Albert Einstein: a biography, Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Stauffer D. Einstein’s theory of surface tension. Annalen der Physik. 2001;10(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3889(200109)10:9%3C731::AID-ANDP731%3E3.0.CO;2-Z

The Long Silencing of Women in Science Continues Today. Literary Hub. Published March 5, 2021. https://lithub.com/the-long-silencing-of-women-in-science-continues-today/

Krstić D., Mileva & Albert Einstein: their love and scientific collaboration, Radovljica: Didakta, 2004.

Elsa Einstein – Death, Husband & Facts. Biography. Published November 1, 2021. https://www.biography.com/history-culture/elsa-einstein

Volume 9: The Berlin Years: Correspondence, January 1919-April 1920 (English translation supplement) page 5. Princeton.edu. Published 2025. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol9-trans/27

Ross MB, Glennon BM, Murciano-Goroff R, Berkes EG, Weinberg BA, Lane JI. Women Are Credited Less in Science than Are Men. Nature. 2022;608:135-145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04966-w

Image Sources

“Mileva Marić.” Author Unknown. 1896. http://www.bhm.ch/en/news_04a.cfm?bid=4&jahr=2006. Accessed April 19, 2025. Public Domain.

“Mileva Marić Einstein and husband Albert.” Author Unknown. 1912. http://ba.e-pics.ethz.ch/latelogin.jspx?records=:33805&r=1448594392396#1448594400592_1 ETH Zurich Archives. CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Mileva and Albert Einstein with their son Hans Albert in the garden: postcard.” Author Unknown. 1904-1905. ETH Library Zurich, Image Archive / Hs_1457-72. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/5117/511767145014/html/ Public Domain.

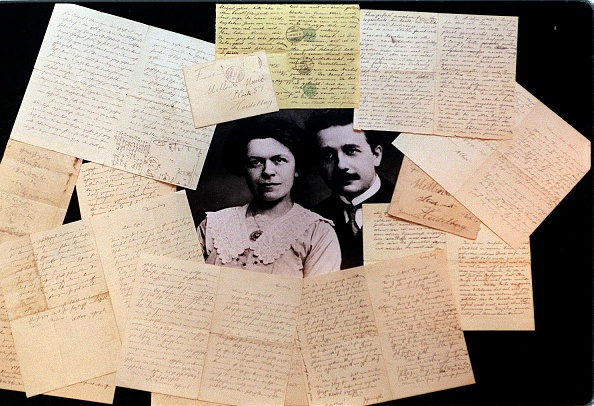

“Einstein Family Correspondence, including Albert Einstein-Mileva Marie[sic] love letters, surround a portrait of the couple, before going under the hammer at Christie’s in New York on November 25, 1996.” 1996. David Cheskin. PA Images/Getty Images. https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/einstein-family-correspondence-including-albert-einstein-news-photo/829881250. Used under License.

“Mileva Reading a Book.” Author Unknown. Date Unknown. https://rinconeducativo.org/en/anniversaries/august-7-1948-death-mileva-maric-how-much-contribute-einsteins-discoveries/. Public domain.

“#nobelformileva.” Li Xinmo https://li-xinmo.com/. 2021. Public Domain.