By Noelle Shorter

You jolt out of sleep in the middle of the night with severe back pain. You feel your abdomen tightening and aching and remember, “I’m almost 9 months pregnant. I must be going into labor!” You frantically wake up your partner, grab the hospital bag you prepared 5 months ago, and rush to the hospital. There, the nurse congratulates you, realizes you are quite far along in labor, and rushes you both to a delivery room. After 2 hours of walking, stretching, breathing, and pushing, you have a beautiful baby boy. You and your partner then stay at the hospital for two days, being monitored and meeting your child, meeting a lactation consultant, and finally getting to go home as a happy family.

Now picture this: you jolt out of sleep, feeling contractions, and think, “Oh no, I didn’t want this to happen here.” You crawl out of your bottom bunk, trying not to disturb the person sleeping above you. You get the attention of the correctional officer on duty and tell them that you think you’re going into labor. She rolls her eyes at you, puts you in a transfer cell, and says someone will be back later to take you to the hospital. After hours of breathing through contractions in the tiny room, another correctional officer comes in, handcuffs you, and takes you to the ambulance, where they shackle your ankles for good measure.5 After finally making it to the hospital room, one of the healthcare workers has the kindness to call your mother, who arrives quickly. However, the correctional officer standing guard at the door says it is against state policy to let her into the delivery room.5 After hours of laboring alone, one ankle shackled to the bed, you finally give birth to a daughter, who is whisked away for extensive tests before you can hold her. When the tests come back clear, you can finally hold her and awkwardly try to breastfeed, still shacked to the bed, in front of the correctional officers.

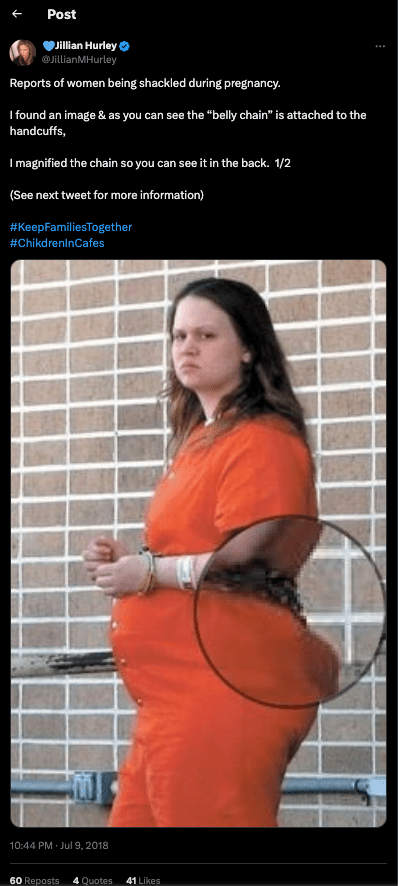

The second story seems like a nightmare. However, it is a reality for thousands of women every year. Many facilities require handcuffs, leg irons, and belly chains or belts on incarcerated women while they are transported to the hospital, even if they are in active labor.5 Many facilities keep at least some of these restraints on during the entire labor, despite the United Nations ruling that “instruments of restraint shall never be used on women during labor, during birth and immediately after birth.”7 Correctional officers are also required to be in the room, but in many facilities they are not required to be female.5 Unfortunately, this maltreatment does not start or end with labor. It begins during pregnancy, with lack of care and appropriate nutrition, and extends to postpartum treatment and separation of mother and child.

Approximately 2,000 women give birth in prisons annually, and 5-10% of women enter prison or jail pregnant.4 That is approximately 58,000 incarcerated pregnant women who need access to specialized care, prenatal diet, and accommodated living conditions.10 One study revealed that women who were given high-quality food experienced fewer complications during pregnancy and labor.11 Despite this, there are limits in jails and prisons on foods like fruits, vegetables, and milk; and multivitamins are not commonly prescribed.5 There are “no federal regulations on the minimum standards for nutrition in state prisons,” so the lack of quality food and prenatal vitamins for incarcerated pregnant women can be swept under the rug.12

For pregnancy-related accommodations in living conditions, most facilities at least require a pregnant inmate to have a bottom bunk. However, in over-crowded facilities, pregnant women end up on top bunks, or even sleeping on the floor.1 Pregnancy is already very physically demanding, so putting pregnant women in living conditions where their physical needs are not met could cause lifelong consequences for mother and child.

Beyond the women who are pregnant or give birth while incarcerated, one study indicated that 25% of incarcerated women are pregnant or gave birth less than a year before entering prison.8 Therefore, women who had a baby just before being incarcerated will most likely be separated from their newborn children. As for women who give birth while incarcerated, they are separated from their children only a few days after birth.2 A mother wants to bond and find comfort in her newborn, especially after going through the traumatic experience of chained labor. They are often denied this experience. One study that interviewed several incarcerated women who were separated from their children reported the mothers saying things like “it feels empty without him/her in my belly,” and “I want to get on parole so I can be a mom.”3 Despite the fact that incarcerated pregnant women usually are not given adequate care, many women in the study said that “everything was fine until I gave birth,” which truly revealed how devastating this child separation is for the mother.3

I want to get on parole so I can be a mom.

Unsurprisingly, the mental health of most incarcerated pregnant women or mothers deteriorates. As many as 80% of pregnant women in a correctional facility experience depression at some point.9 More specifically, postpartum depression is very prevalent, likely aggravated by the isolation from family and friends in the correctional facilities. Increased stress during pregnancy and the postpartum period, a lack of support, transfers between correctional facilities and hospitals, and separation from their child all contribute to maternal depression.8 The mother is not the only affected party, as children of incarcerated mothers are more likely to be anxious, depressed, and withdrawn, especially if separated from their mother during infancy or toddlerhood.6

Despite all of this, there is hope for a change in these disparities that has started with the creation of nurseries for incarcerated mothers. Nine states now have these so-called “prison nurseries,” in which mothers are able to serve time while being with their newborns.4 Prison nurseries are special housing unit inside the prison, where a mother can parent her baby alongside other incarcerated new mothers.13 The states with these programs already built include California, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Nebraska, New York, South Dakota, Washington, and West Virginia.13 There are also Community-Based Residential Parenting (CBRP) programs in Alabama, California, Connecticut, Illinois, North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Vermont.13 Unlike prison nurseries, CBRP programs are not located inside prisons. Instead, CBRPs are separate facilities, usually run by non-profits, that allow mother and child to live together under supervision.13 Children who spent their first 1-18 months in a prison nursery, rather than being separated, had much lower anxiety/depression scores as preschoolers.6 On the opposite spectrum, children who were separated from their incarcerated mothers showed a higher prevalence of insecure attachment (mistrust, avoidance, and anxiety that arises due to past interactions) towards their temporary guardians and mothers.6 Therefore, studies show that both prison nurseries and CBRP programs have very positive impacts on both children and mothers. These programs have introduced humane changes that have helped the welfare of incarcerated mothers and their children. However, more needs to be done. Including states’ prison nurseries and CBRP programs, only 14 out of 50 states provide mother-child incarceration/CBRP. Because such clearly positive results are seen when mothers and children can remain together, these facilities are needed in every state in the US.

Works Cited

- Amy Yurkanin. (2022, September 8). Pregnant women held for months in one Alabama jail to protect fetuses from drugs. Al. https://www.al.com/news/2022/09/pregnant-women-held-for-months-in-one-alabama-jail-to-protect-fetuses-from-drugs.html

- Carlson, J. R. (2018). Prison Nurseries: A Way to Reduce Recidivism. The Prison Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885518812694

- Chambers, A. N. (2009, December 18). Impact of Forced Separation Policy on Incarcerated Postpartum Mothers. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1527154409351592?casa_token=kxLokm6b5r8AAAAA:LuQJZAms5PK3NBTbBMsjwkuQz2t0c_ksxy2VH5xEPfn4Mz965jDd1KMUlfYEO83oViRGZApjfyPP

- Clarke, J. G., & Simon, R. E. (2013, September 1). Shackling and separation: Motherhood in prison. Journal of Ethics | American Medical Association. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/shackling-and-separation-motherhood-prison/2013-09#:~:text=Between%205%20and%2010%20percent,unacceptable%20in%20any%20other%20circumstance

- Ferszt, G.G., & Clarke, J.G. (2012). Health Care of Pregnant Women in U.S. State Prisons. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23(2), 557-569. doi:10.1353/hpu.2012.0048.

- Goshin, L. S., Byrne, M. W., & Blanchard-Lewis, B. (2014). Preschool Outcomes of Children Who Lived as Infants in a Prison Nursery. The Prison Journal, 94(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885514524692

- Hall, R. C. H., Friedman, S. H., Jain, A. (2015, September 1). Pregnant women and the use of corrections restraints and Substance Use Commitment. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://jaapl.org/content/43/3/359

- Kotlar, B., Kornrich, R., Deneen, M., Kenner, C., Theis, L., von Esenwein, S., & Webb-Girard, A. (2015). Meeting Incarcerated Women’s Needs For Pregnancy-Related and Postpartum Services: Challenges and Opportunities. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(4), 221–225. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48576281

- Mukherjee S, Pierre-Victor D, Bahelah R, Madhivanan P. Mental health issues among pregnant women in correctional facilities: a systematic review. Women Health. 2014;54(8):816-42. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.932894. PMID: 25190332.

- Pregnancy and childbirth in prison. Penal Reform International. (2022, August 24). https://www.penalreform.org/global-prison-trends-2022/pregnancy-and-childbirth/

- Rebecca J. Shlafer, Jamie Stang, Danielle Dallaire, Catherine A. Forestell, and Wendy Hellerstedt.

- Best Practices for Nutrition Care of Pregnant Women in Prison. Journal of Correctional Health Care. Jul 2017.297-304. http://doi.org/10.1177/1078345817716567

- Shlafer, R. J., Stang, J., Dallaire, D., Forestell, C. A., & Hellerstedt, W. (2017). Best practices for nutrition care of pregnant women in prison. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 23(3), 297-304.13) Women’s Prison Association (Ed.). (n.d.). Mothers, infants and imprisonment – prison legal news. Prison Legal News. https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/media/publications/womens_prison_assoc_report_on_prison_nurseries_and_community_alternatives_2009.pdf

Image Reference

“A Pregnant Woman in Prison.” By Arts and Catfrs/Shutterstock. https://www.shutterstock.com/image-vector/pregnant-woman-prison-vector-image-2119331099. Used under License.